Yellow Peril or Yellow Blessing?

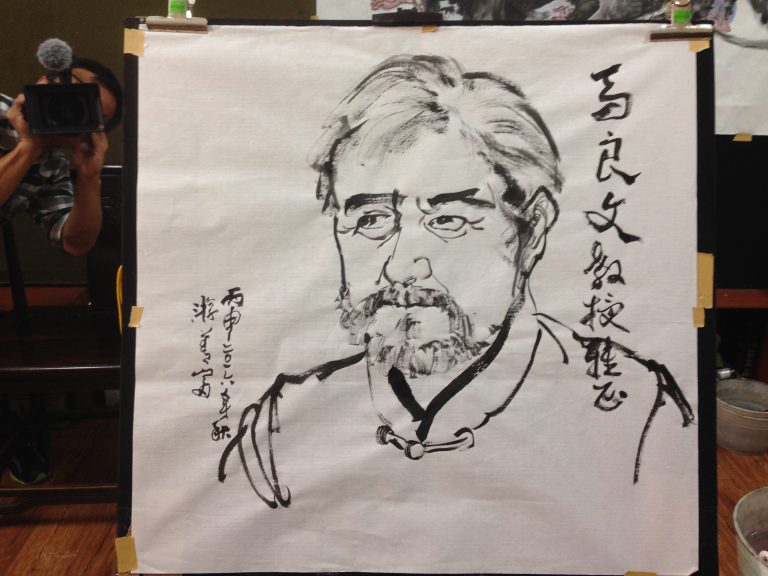

V.V.Maliavin

Yellow Peril or Yellow Blessing?

Images of Eastern Asia in Russia at the Turn of the XXth Century[1].

Paper presented at the Conference “New Perspectives on East Asian Studies“, Taipei, 2012, June 1-2.

Since the latter half of the XIXth century Russia’s attitude to Eastern Asia and Far East in particular has been the hotly debated issue in Russian society. For many reasons, mainly political, it has been poorly explored in Russian historiography[2].This was a multi-faceted discussion which allowed for quite divergent opinions and sudden changes of agenda. To a certain degree it reflected the general attitude of Europeans towards Asian civilizations at that time of colonial expansionism. Yet to a much larger degree it was a product of mentality and political struggle peculiar to Russia. Basically, it was a vital part of Russia’s search for identity. Quite obvious political implications of this discussion as well as its participants’ limited knowledge of Asia inevitably rendered it rather superficial by modern standards. What we are dealing with is not so much carefully constructed theories but emotional, often passionate, statements that appeal to mental stereotypes, habitual phobias and play of imagination. Precisely for this reason they possess an extraordinary vitality. They are fully alive and in many ways determine Russia’s Eastern policy and public opinion even today.

Historically, this dispute reached its culmination in the beginning of the XXth century when Russia came in direct contact with the Far Eastern peoples and felt the urgent need to define her strategy in this region. Russia’s penetration into China and the failure in the military conflict with Japan were the most important factors of Russia’s reevaluation of her Eastern policy. Yet the issue of Russia’s relation to the Far East was determined mostly by the traditional contradiction between the two faces of Russia: European and Asiatic.

It is only to be expected that Russia’s Westernized elite all too quickly picked up the myth of the “Yellow Peril” born in the West. J.S.Mill castigated Chinese civilization as despotic and depriving people of all rights and liberties. Influenced by Mill, a leader of Russian revolutionary intelligentsia at that time A.I.Herzen by 1855 was already warning fellow Russians of the coming hordes of Asians who will destroy Western civilization and its main spiritual treasure – Christianity. The coming catastrophe seemed all the more inevitable since Herzen in a typically Russian way was rather skeptical about European ideals of progress and did not believe in the spiritual potential of Christianity. Since that time the invasion of the Yellow race was feared by Russian intellectuals for allegedly “spiritless” (bezdukhovny) nature of Asiatic civilization. Philosopher Solovyov predicted the invasion of the Yellow race that will destroy Russia. Solovyov took a morbid delight in describing the scene’s of Russia’s terrible fate in the hands of the new barbarians from the East.

Solovyov’s warnings seemed to come true during Russia’s war with Japan. This defeat prompted an influential Russian writer D.Merezhkovsky to produce a seminal article “The coming petty-man” (Griaduschy kham). Chinese civilization was depicted by Merezhkovsky as a hotbed of vulgar positivist thinking that threatens to destroy the last strongholds of Western spirituality.

The Yellow Peril myth strikes us as flatly dogmatic, a symptom of the phobias lacking any real understanding of Asian peoples and cultures let alone the profound differences between their cultural traditions. Moreover, at closer inspection it turns out to be a projection of Western mentality on Asian life. Far Eastern nations were sanctioned by Russian religious thinkers for their “positivism” and “petty-bourgeois” habits exactly because this life style and way of thinking under the name meschanstvo was the main target of intelligentsia’s social criticism at home. Much more surprising is the inability of the intelligentsia’s gurus to see that they were attacking in fact something that was quite familiar to the West and even constituted the core of the modern Western civilization. Merezhkovsky was the first to declare that the Yellow invasion will be a peaceful victory of the bona fide “yellow-faced positivists” over the Western positivists. He wrote:

“While nowadays Chinese are willing to imitate Europeans, the time will come when Europeans will be looking like imitating Chinese”1′.

So, while projecting on the Asian peoples the most salient negative features of the modern Western mind, above all its well disguised barbarity, the Yellow Peril myth points to some deep contradictions of modernization process. The man of the Modern Age is split into the Superman who subdues the natural world to the power of his will and the Underman – a timid consumer, a slave to his desires who leads in fact an animal-like existence. It is precisely the power of technology and its political counterpart, representative democracy, that stand out as the common denominator of these incompatible positions. No wonder then that Superman and Underman merge in the image of the triumphant “petty-man” from the East – an easy way, in fact, to resolve in imagination the tensions unsolvable in reality.

Let us recall that the social position of Russian intellectuals was in many ways no less contradictory: while striving, as a champion of reason, for a public recognition, a role of statesman and the leader of the nation, they were doomed to remain fundamentally marginal figures both for the aristocrats and the common folk. This contradiction quite often was to be overcome through mystical overtones so characteristic of the Yellow Peril fantasy in Russia during the first two decades of the XXth century. It is particularly true of Symbolism – a leading movement in Russian literature and art at that time. A.Bely in his famous novel “Peterburg” (1913) mentions “yellow faces” who creep in the city and invisibly govern it. During the First World War the leader of the Symbolist circle Vyacheslav Ivanov declared that the German High Command was connected to some “secret order of Oriental magicians”, perhaps the high lamas of Tibet, whose aim was to destroy Russia[3]. This idea lingered on in many guises. Already by the time of revolution the Russian painter and mystic Nikolai Roerich gave it a radically new twist: he depicted Tibetan “secret order” of supreme magicians as the dwellers of mystical Shambala, an alternative power of salvation belonging to the “realm of the night”.

Alongside this negative and pessimistic, even apocalyptic, vision of Asia there has always existed in Russia an alternative vision which called for a rapprochement and even union of Russia and the Far Eastern nations.

The most well-known spokesman for these, so to say, Eurasians avant la l?ttre was, perhaps, count Esper Ukhtomsky who firmly believed in the deep affinity between Russian and Far Eastern civilizations. Ukhtomsky found a proof of this affinity in the paramount importance of monarchy in both Russia and Asia. The myth of the White Tsar served for Ukhtomsky a compelling evidence of that “natural” union of Russia and Asia as well as Russia’s leading role in this part of the world. Moreover, for Ukhtomsky monarchic institutions and the veneration of saints were visible signs of a much deeper common foundation of Russian and Asian sensitivity in general. In Russia, he wrote, “everything that runs deep in the life of the people is permeated with the Oriental conceptions and beliefs, with the quest for the supreme forms of being… utterly different from the materialistic thinking of modern Europeans”[4].Writing at the time of the Boxer Rebellion in China, Ukhtomsky claimed that Russia was delivering a kind of “active faith” to the peoples of Asia who are falling short of the “internal creative work”. This “activist faith” of Russians, is based, nevertheless, on the “creative calmness” of the soul which is familiar to Asians since time immemorial[5].

Ukhtomsky’s view has interesting spatial implications. It places Russia, as it were, at the periphery of the world civilizations, in what he calls “the primordial place at the boundaries of the contradictory cultures”, between East and West[6]. The union of Russia and China is to be achieved through their marginal zones with the help of the people with obscure and ambiguous identity: kossaks, nomads, wanderers of all kinds. “Our Oriental pioneers, Ukhtomsky writes, discovered the world which was not new; they discovered often familiar from their childhood by their appearance and speech, by their customs and manners good-tempered people of alien tribes. It was easy, depending on circumstances, to fight or live peacefully with them..”[7].

Another conservative Russian journalist, N. Syromiatnikov, writing also in 1900, made even more explicit statement on the necessity to reach a positive balance in Russia-China relations. “For the completion of the world history, declared Syromiatnikov, it is necessary to equalize the potentials of the East and the West so that the new Mongol will feel at home in Europe and the new European will feel at home in the heart of Asia. But this will happen only after the tremendous hidden energy of China will run out because the psychic energy of the West where separate individuals stand out like poorly combed hair is no match for it”[8].

A bit later the idea of the Russian-Chinese fusion was reinforced by I.Levitov’s project of establishing in trans-baykal region a separate “Yellow Russia” destined to become a Russian-Chinese melting-pot. The most radical effort to establish the joint Russian-Chinese-Mongolian empire was a short-lived military campaign of the White Army commander baron Roman Ungern, a devout foe of the pro-communist Far Eastern Republic who was a de-facto ruler of Central Mongolia from March to June 1921. Ungern’s aim was to restore Chyngiz-khan’s empire in the form of the pan-eurasian “Middle Kingdom” with the White Tsar on top and Orthodox Christianity and Lamaism coexisting as two official religions. Strategically Ungern had no chance to win over the Red Army: he was betrayed by both Russians and Mongols, taken prisoner and executed in Russia. Besides, Ungern’s ideological program had a serious flaw common to all conservative nationalisms: he intended to build a technically modernized state on the basis of traditional institutions[9]. Be as it may, it is in a sense a typically “eurasian” situation: a German Russian trying to bring together Russia and China with the help of Mongols!

Despite obvious political connotations of Ukhtomsky’s and similar geopolitical theories, the idea of Russia’s organic unity with Asian civilizations had a wide appeal in Russian society. It found, among others, a sympathetic response in such devout enemy of state in general and Russian government in particular as Leo Tolstoy. This great writer was indifferent to geopolitical considerations but he found in the Oriental “immanentism” so frightening to Russian Westerners, a veneration of life which was the true foundation of all religions. Tolstoy expressed the hope that Chinese people will preserve their traditional China because “what Europeans call stagnation of China is thousand times better than the universal hatred and animosity created by Christian societies”. The Chinese, Tolstoy wrote, should not give way to the temptation of the so called “democratic liberties”. They must establish new forms of social life in the spirit of genuine liberty and supreme moral law: the refusal of violence.

This in many ways typically Russian idea of Christian-Taoist and Christian-Buddhist synthesis acquired a much more sophisticated form and truly global dimension in the philosophy of Russian expatriate painter Nikolai Roerich whose views are alive and influential in modern Russia. The idea of such synthesis was further developed by one more German Russian of Eurasian brand (once again a typically Russian alloy) Eugene Schiffers (1934-1996).

The fact is that the common Russians have always been quite open to Asia, Russian folklore located blissful lands (like Belovodie, Nikanskoe zarstvo etc.) somewhere far in the East and Russian eastward expansion was at least partially motivated by the desire to find these folk utopias[10]. No wonder, that during Revolution which was marked by the revival of folklore traditions, the poets who relied on them – S.Yesenin, N. Klyuev, N. Oreshin and others – equaled the mentality and values of Russian peasants to those of Scythians – the ancient nomad tribe opposed by the Russian folk romantics to the “decadent” European civilization. The most mature exposition of this line of “pre-eurasian” thought is the poem “Scythians” by Alexander Blok. The poem, written in January 1918, starts and finishes with Russia’s appeal to Europe to “come to peaceful embrace”:

«But if this appeal is rejected by Europe because of her self-love and narrow-mindedness, then Russians will change their attitude with disastrous consequences for the West. Europe will be crushed by the Yellow Peril while Russia will remain an indifferent witness to this catastrophe:

Who are those “Russians-Scythians”? Many commentators identified them with Asian nomads. Yet they are clearly distinguished from the “Huns” who represent Asian barbarism in its pure form. In the preface to the first edition written by Mstislavsky and Ivanov-Razumnik Scythians are described poetically – as the free people of the steppes embracing the infinity of the world[11]. They are essentially marginal, ambiguous, changeable and shrewd people with obscure identity roaming between Asia and Europe. Once again we come across the theme of the priority of periphery in Russian-Asian relations. That makes Russians a nomadic people by their mentality, sensitive, communicative, capable of playing with all kinds of identities. Initially, Blok’s poem read “rogues” in place of “scythes”: “Yes, we are rogues, we are Asians…”.

Interestingly, this is very much true of Russia’s practical politics towards both Europe and Asia. Russians pose as Europeans to Europe when on friendly terms and immediately turn to their Asian resources in case of conflict. The same, mutatis mutandis, is true of Russia’s Asian policy.

A fascinating question emerges: why did this rich variety of “Eurasian” concepts of Russia’s strategy remain just a stock of guesses and fantasies apart from Russia’s mainstream self-images and strategic theories despite the fact that it actually determined many practical steps and decisions in Russia’s home and foreign policy? Apparently, the answer is the lack of the proper theoretical framework for this historical perspective. The search for such a framework remains one of the most urgent issues in contemporary global strategy. Curiously, contemporary, so called “post-foundational” concept of politics with its sharp distinction of politics and “the political” and the affirmation of the “Machiavellian moment” in politics, the self-differential nature of the political provides a promising perspective for exploring this “Eurasian” component in political theory[12].

[1] The author is grateful to Mss. Chen Chia-wei for precious contributions to this paper and its presentation at the conference.

[2] Interestingly, no systematic study of this issue has appeared until now in Russia. In Western literature the political implications of Russia’s expansion in Asia has been investigated by D. Schlimmelpenninck van der Oye and its ideological dimensions in lesser details by M. Sarkisyanz, M. Larouelle and others. See: M.Sarkisyanz. Russland und der Messianismus des Oriens. Der Verlag J.C.B.Mohr, 1955; Schlimmelpenninck van der Oye, Towards the Rising Sun. Russian Ideologies of Empire and the Path to War with Japan. Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2001; M.Larouelle , Russian Eurasianism. The Ideology of Empire. Washington D.C. Woodrow Wilson Press, 2008; M.Larouelle ,”The White Tsar”: Romantic Imperialism in Russia’s Legitimizing of Conquering the Far East. — Acta Slavica Iaponica. Vol.25, 2008.

1′ Merezhkovsky, D.S. Bolnaya Rossia (Sick Russia). Moscow, 1992. P. 18.

[3] G. Obatnin. Vyachaslav Ivanov – mystic. Moscow, 2000. P.131-132 (in Russian). Vyacheslav Ivanov held a fairly uncommon view that German and Chinese mentality are quite similar and because of this Germany is constantly trying to use China as an ally in the struggle against Russia. The basis for this similarity was, according to Ivanov, sympathy for the “subjective idealism” and “idealistic normativism” which turn society into a kind of an anthill governed by the “common biological reason and biological will”. Vyacheslav Ivanov. Rodnoe i vselernskoe. Mosckva: Progress, 1994. P.379 (in Russian).

[4] E.E.Ukhtomsky. K sobytiam v Kitae. Moscow:Librokom, 2011, p. 46 (reprint of 1900 edition, in Russian).

[5] Ibid., p. 49, 83.

[6] Ibid., p.48.

[7] Ibid., p.79.

[8] Novoe Vremia. , 1900, March 5.

[9] Various previously unknown materials related to Ungern’s life and political ideas are collected in recently published book: Legendarny baron: neizvestnie stranitsy grazhdanskoi voiny. Ed. by S.L.Kuzmin. Moscow: KMK Publ. 2004 (in Russian). These materials reveal that Ungern, contrary to accusations raised against him in Communist Russia, was not willing to cooperate with the Japanese. It seems, Ungern’s Middle Kingdom, like the medieval Mongolian empire, was not supposed to include Japan.

[10] For a detailed account of “Asian Utopias” in Russian folklore see: K.Chistov, Russkaia narodnaia utopia. Sankt-Peterburg: Dmitry Bulanin, 2003 (in Russian).

[11] Semiotika i avangard. Antologia. Moscow: Kultura, 2010. P. 372-373. (in Russian).

[12] See: Oliver Marchart. Post-foundational Political Thought. Edinburg: Edinburg University Press, 2007.