Vladimir Ern and the Quest for a Universal Philosophy

Vladimir Maliavin

Эта давняя статья, опубликованная в 2000 г. и существующая только по-английски, содержит ряд важных положений, которые позволяют в новом свете оценить место христианства в современном мире и его отношение к восточным традициям. Надеюсь, что читатели, владеющие английским языком, уделят ей внимание. Со своей стороны, я постараюсь в ближайшем будущем изложить и развить ее главные темы по-русски. Сноски и библиографию к статье можно найти в ее первой публикации.

Logos: The Core of the Russian Tradition

Ever since the Russian philosophical tradition came into being around the middle of the 19th century Russian thought has been asserting itself, firstly, as a response and an alternative to Western thinking and, secondly, as a fulfillment and overcoming of the latter. For the present purposes, suffice it to quote the classical statement made in 1852 by Ivan Kireevsky, the founder of the Slavophile school:

“The very triumph of the European mind has laid bare the one- sidedness of its fundamental pursuits, for in spite of the enormity of partial discoveries and the successes of science they have had thus far only a negative significance for inner knowledge”.

These words show well the fundamental traits of Russian nativist thinking: a recognition of Western civilization’s “partial achievements” and a negative evaluation of its overall nature. Such an attitude obviously calls for a new and perfected vision of reality. In fact, Kireevsky himself is known to have “overcome” in the course of his intellectual development the latest fruit of Western learning of that time — Hegel’s system of philosophy. This is where all Russian indigenous thought begins: at the point where hegelian reflection exhausts itself and humankind reaches “the end of history”. In this post-hegelian world all dialectical distinctions are bound to lose their efficiency and the lost integrity of human activity is once again linked together with the ideal of human perfection — perfection of an essentially religious nature. Kireevsky calls for reevaluating Russia’s ahistorical “archaic” existence as a post-historical one. This radical change of perspective would make possible the actual realization of a philosophic synthesis, a synthesis which had been achieved in the West only conceptually.

This peculiar stance of Russian thought reached its maturity in the works of Vladimir Soloviov (1853-1900), who is often called — rightly, I believe — the founder of Russian speculative philosophy. He, moreover, exerted a many-sided influence on literary and artistic movements in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century. Soloviov started his philosophical career as a successor to the Slavophile tradition founded by I. Kireevsky and his friend A. Khomiakov. He directed a torrent of vehement criticism against Western positivism and developed a philosophical system based on the notion of “integral knowledge”. Yet Soloviov’s appreciation of the “organic integrity in thought and culture did not make a conservative of him. On the contrary, he endeavored to expose the evils of Russian nationalism and the official Orthodox Church — an undertaking for which even up to the present he continues to be widely acclaimed in the West as a paragon of democracy while in Russia he remains under constant attack from the nationalist camp. This convergence of nativist thinking and a universal outlook, so central to his thought, is one of the most remarkable facts of Russian intellectual history.

Soloviov’s metaphysics is based primarily on the Platonic tradition with borrowings from Schelling and, to a lesser degree, Schopenhauer and Hartmann. Its key concept is Logos — a term which in Platonism designates philosophic truth but in Christianity is specifically linked with divine creativity and the Evangelic message. The Christian Logos points to the essence of the mediation between God and humanity as personified by Jesus Christ. Hence, akin to the Logos of the Greek philosophers, it refers to the truth or the true meaning of a discourse which is somehow antecedent to human speech and transcends it. It is perfectly objective but is not susceptible to objectification. It represents “the inner light and the Law of life”, “ the center of world history”, “the fullness of time and perfection”. In Soloviov’s system Logos acquired a more specific meaning: it represents the active principle of the union of God and humanity (bogochelovechestvo) personified by Jesus Christ while its passive counterpart is identified with Sophia, the “Divine wisdom” which corresponds to the “eternal Feminine” and the Earth. The doctrines of Logos and Sophia were specifically elaborated by Soloviov in relation to his phenomenology of Divine.

Soloviov’s philosophical project is essentially an attempt to unite the Christian doctrine of Logos with speculative thinking. True philosophy, Soloviov declares, is “free theosophy.” In his major philosophical works, The Philosophical Principles of Integral Knowledge and Critique of Abstract Principles, he repeatedly lays emphasis on the ontological connotations of Logos. The latter is conceived by the Russian thinker as “the absolute first principle” which “contains in itself its own definitions of every essence and represents the absolute prim of all being and knowing”. Thus, Logos becomes the foundation of Soloviov’s central idea of “all-unity” – a rather complex notion which essentially refers to the unity in multiplicity and the presence of God in the finite world. Consequently, Logos is essentially a relationship — an unconditional, meta-logical “inner relation between the knowing subject and the thing known” which precedes and transcends all actual states of consciousness. Its origin is the relation of a “supra» existent” God to His posited essence in which God knows Himself. Thus, the concept of Logos reveals the mystery of the Christian Trinity. As a determining cause of everything Logos cannot be represented in any form of objective knowledge but is directly experienced as “the inner conviction of one’s reality” through this experience of one’s relation to the “Other”. In fact, man’s ego, according to Soloviov, is merely “a support for something other than and higher than itself”.

According to Soloviov, Logos is manifested in human understanding through the combination of the three enactments of the human spirit: those of faith,imagination and creativity. These three aspects of knowledge unfold in three successive stages of the acquisition of knowledge. Originally Logos represents the Selfs «inner relation to the object of knowing” and this link “lies deeper than any actual consciousness. This stage of faith is marked by an “inner conviction in the existence of being” which is tantamount to the freedom of the knowing subject. The next stage corresponds to the “imagining of object” by means of which a constant image of the object in the subject’s mind is established. In the final stage, under the influence of sensual perception this ideal image takes on its actual, relative and conditional manifestation which belongs to the realm of empirical experience.

It should now be easy to see why Soloviov rejects empiricism: the latter, he argues, in attempting to highlight the achievements of the positive sciences, in fact undercuts them in so far as it reduces the world of appearances to mere sensations. Rationalism, in Soloviov’s opinion, has its own inborn limitations. since it reduces the world of ideas to the sphere of formal thought Integral knowledge implanted in the human mind (though never constructed by it!) by Logos is characterized by Soloviov as “mystical” in nature. Soloviov’s epistemology evidently resembles Schelling’s teaching on the intellectual intuition but the Russian thinker never attempted to explain how “mystical knowledge” is related to revelation, on the one hand, and intuition,on the other, nor did he indicate where one might find the boundary separating the two.

The hidden influences in Soloviov’s work notwithstanding, his thought brings philosophical reflection to its historical point of departure—the premise of God’s existence – without solving the age-old problem of theological dogmatism. This failure is due, in part, to the incompatibility of two different kinds of reasoning: one concerned with the equal and essentially qualitative units of reality, the other with the hierarchy of qualitatively distinct levels of existence within a single entity or, in other words, the wholeness of being.

A few years after Soloviov’s death in 1900 one of his most brilliant followers, Vladimir Ern (1882-1917), came forward with a new and much more radical version of the philosophy of Logos. Ern’s passionate apology in defense of the Orthodox tradition’s spitiual foundations, universal in their metaphysical applications and historic appeal,was quite in tune with Soloviov’s message and helped him in gaining the reputation of “philosopher-confessor” — a label rarely used among Western philosophers. In Ern’s philosophical works, which present a unique combination of methodical reflection and poetical exaltation, one can find the most comprehensive and at the same time polemical formulations of the traditional patterns of Russian thinking nourished by Orthodox theology.

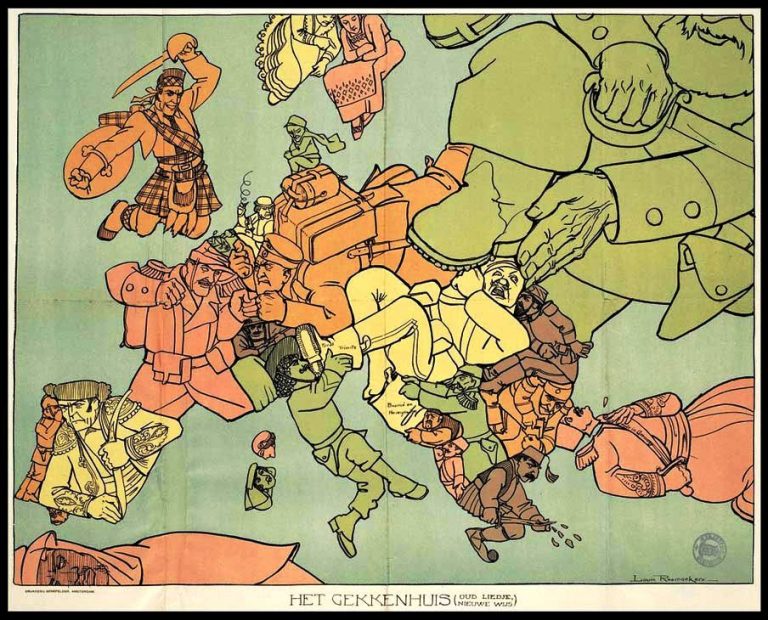

In his time Ern was branded by his opponents (notably S. Frank and S. Hessen) as an advocate of “Russian nationalism”. Even today Vladimir Ern is most widely associated with an unreserved hostility towards German idealist philosophy, especially in its Kantian and Hegelian versions. Yet this notorious label as well as attempts to oppose Ern’ s “nationalism” to Soloviov’s “universalism” do no justice at all to Ern’s philosophical position. It is true that Ern’s views were shaped in the course of his polemics against the proponents of Russia’s Neo-Kantian school, a group of young philosophers who comprised the editorial board of the journal “Logos” — S.Hessen, F. Stepun, B.Yakovenko et al. These polemics, abruptly interrupted by Ern’s premature death and the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, represent in and of itself an illuminating landmark in Russian intellectual history. Yet their historical significance extends greatly beyond the formal scope of the polemics related to the neo-kantian Problematik. Ern’s criticism exposed, or at least was aimed at exposing, some fundamental differences between types of thinking and cultural patterns of Europe and Russia—differences that are no less relevant and disturbing today than they were a century ago as the conflicts in Yugoslavia and Russia’s growing alienation from the European community show.

As a matter of fact, Ern’s alleged “germanophobia” has an important positive side, i.e., it represents an attempt to define the specific features of Russian thought in terms of a systematic philosophical outlook and a peculiar spiritual and cultural tradition. Moreover, this positive aspect can be discerned even to Ern’s negation of “Germanism” (viewed as the quintessence of Western philosophical reflection). According to Ern, the struggle between the guiding forces of Russian and German traditions is destined to liberate the German nation (and the whole of Europe) from the yoke of “suffocating rationalism” but this victory is destined to help Russians to discover for themselves “the pure gold of humanity glittering on the peaks of German culture”. Moreover, like Soloviov, Ern regards Catholicism as the Western offshoot of the very idea of the Logos which nourished the Orthodox tradition. In fact, he sees no principal difference between these two branches of Christianity. In the final account for Ern, as is always the case with lovers of Russian spirituality, Russia’s task is universal and a fortiori liberating. Humankind, Ern never ceases to insist, must be liberated through the disclosure and appropriation of the “alternative” truth. The nature of Russian thought, Ern claims, is determined by an acute awareness of the mutual incompatibility of the superficial rationalism of the West and the Eastern quest for “ontological truth”.

Ern has managed to reduce his theory of the East-West dichotomy in philosophy to a set of binary oppositions, which may appear at first glance overly simplistic. The basic opposition is between what he refers to as “rationalism», i.e., a determining factor in modem Western thought, and the “Logos» or “logism”, the characteristic feature of Russian thinking as shaped by Orthodox spirituality. Unfortunately, neither Soloviov nor Ern provides a systematic definition of this fundamental concept of the Russian tradition. Curiously enough, while Ern consistently opposes Logos to Ratio, Soloviov himself often used these terms synonymously.

The difficulty with Soloviov’s (together with other representatives of this philosophic tradition in Russia) concept of Logos is that it is an a priori, one could say even a dogmatically postulated notion which fulfills, once it is accepted, a perfectly rational function within Soloviov’s system. It is endowed with a kind of meta-logical rationality peculiar to mystical thought: In more general terms rationality as the apriorical structure of living experience is a popular theme in modem phenomenology from M. Scheler to M. Merleau-Ponty. The problem with it is that at the level of philosophical speculation it yields somewhat ambiguous results. Historically it nowhere exists in “pure” form but is always defined or, one should say, “colored” by cultural conventions.

Is it possible, then, to dissociate Logos from Ratio? Soloviov does not provide any clear descriptions of this procedure and seemingly does not even conceive of such a possibility since he uses both terms interchangeably. Thus, when Vladimir Ern, following Soloviov, singles out the term “rationalism” as a primary target of his criticism he makes a rather unfortunate choice. For, though on the one hand, he is striving to be impeccably reasonable, on the other, he is in fact arguing against any and all kinds of purely humanistic and formally constructed knowledge. In the course of his polemics against Russian Neo-Kantians Ern has invented or appropriated many other terms which designate various aspects of Western “rationalism” These include: (1) “meonism” (derived from the Platonic concept of “mean» or non-being) which refers to the empty or non-existent nature of reality “constructed” in German idealism; (2) “immanentism” or “phenomenalism”一notions which point to the lack of a transcendent reality in critical philosophy; (3) “psychologism” and “impersonalism” which signify the dissolution of personality as a spiritual entity or person’s inner core. The designation of modem Western thinking as “immanentism” has gained especially wide popularity in nativist Russian thought. Original Russian thought itself (as distinguished from Russian imitations of Western philosophy), is endowed, in Ern’s works, with qualities opposed to its Western counterpart. It is, rather, based on the “ontology of knowledge” and addresses the noumenal dimension of experience, thereby dispensing with all forms of psychologism; it is essentially personalistic, stressing the communion of human and divine aspects of being.

As a critic of Western philosophy Ern is most anxious to expose the fallacy of Kant’s epistemology. His anti-kantian undertaking is directed primarily at the thesis of the transcendental subject’s autonomy. This thesis is both central to Kant’s thought and problematic in its very nature. In Ern’s opinion, Kant’s “critical philosophy” is utterly uncritical in taking for granted the data of sciences which constitute conditions for Kant’s transcendentalism. Whatever these conditions are, Kant’s critical reflection, by appropriating a certain content, creates an unbridgeable gap between itself and the world of objects. No object can serve as a point of departure for theoretical thought, concludes The validity of Ern’s argument depends of course on whether we admit the existence of the irretrievable contradiction between the constituting “I” and the constituted “Ego”. Philosophical opinion on this issue has always been and still remains divided. As for Ern, he considers this gap a deadly blow to a genuine humanness in man. Consequently, modem rationalism as a manifestation, according to Ern’s definition, of “thought’s self-determination» is for him illusory and arbitrary from the very beginning. But its self-imposing nature is confirmed by the ratio’s constant (not to say maniacal) willingness to subjugate reality, whatever that may be, to the abstract self-image of thought. It represents an attempt as groundless and, therefore, doomed to failure, as it is aggressive and destructive in regard to the very humanness of humans. It was Kant’s transcendental project, Ern declares, that gave rise to German militarism.

In tracing the roots of modem Western rationalism Ern goes back to Descartes. Cartesian ratio, he argues, is a contemplation of the essence of thought as pure object. It represents an “absolute passivity,” a “dead scheme of judgment, a view trapped in the still point of its own chimeric vision, incapable of any change/18) Ern concedes that there are two ways of substantiating this compelling power of rationalist thought. The first is to admit that thought’s self-image corresponds to its essence. Accepting this option would mean, according to Ern, abandoning the rationalist project altogether. The second possibility is the purely affective intuition of doubt which signifies the spontaneous “convergence of subjective experience and the objective order of the universe,the instantaneous penetration into the hidden mystery of the world. Yet such “empty doubt”, Ern holds, is irrelevant to philosophical reflection.

Ern’ s conclusion is straightforward and brooks no compromise: to engage in a search for some kind of external correlate of thought Is an illusion; the real image of thought is an all-embracing sphere. “That is what the absolute, divine freedom of thought consists in”, Ern writes,“and if there were at least one point pertaining to it a priori, thought would lose its freedom once and for all”.

It is tempting to test Ern’s bold statements by the rigorous means of rationalist discourse itself. It is obvious, however, that this discourse would allow for quite a variety of interpretations. Moreover, to refute or justify his concepts in terms of logical consistency would amount to missing, perhaps, their most important point——the primary value of freedom—for modem rationalism has been motivated by values which lay outside the scope of pure reflection. A more plausible way is to explore “the philosophical alternative” suggested by Ern. A new comparative perspective resulting from this study can provide an impetus for reevaluating the very idea of philosophy and — who knows? — an opportunity for the reconciliation of opposing traditions.

In the concluding essay of his first book “The Struggle for Logos” (1911) Ern draws a grim picture of the modern intellectual crisis. The avatars of rationalism have severed humanity’s ties with Nature, the source of creativity, and are now “suspended” by the thread of the transcendental subject over a dark abyss—an abyss of life deprived of Form. Technocratic civilization has swallowed culture, leaving no space for human creativity as a living synthesis of Form and Matter. Man has been denied access to the sacred depth of his experience. All this means, Ern argues, that humanity is actually forced to strive for a “philosophy of Logos” and he enumerates the latter’s main traits. In addition to the features already familiar to us such as personalism and “ontologism” or “realism”, he mentions the organic model of reality, symbolism (as opposed to the schematism of the ratio) and the ideal of the “internally intensified” or qualitatively defined life. This latter is exemplified, not surprisingly, by religious ascetics and saintly individuals (Ern confronts this aspect of Logos with the rationalistic search for abstract norms). Finally, Ern opposes the static nature of rationalist thought with the dynamism of Logos, a dynamism which presupposes temporal disruptions and “a catastrophic model of history.

Finally, Ern observes that the principles of the “philosophy of Logos” can be found in the teachings of the Church fathers. The real task of contemporary thought, however, is not to go back to early Christianity but to create a new philosophy capable of restoring the basic values of human existence. The above-mentioned aspects of “Logos-inspired thinking”can be analyzed in terms of two broad categories: the theoiy of knowledge and the theory of action (history). The following represents a tentative evaluation of these two dimensions of Logos.

An Ontology of Knowledge: Universal as Personal

The idea of all-unity together with a kind of integral, “ontological” or “living” knowledge is the backbone of the Russian philosophical tradition. This idea! has both profound roots in Orthodox spirituality and immediate practical applications for the cultural self-identity of Russians. Since Kireevsky’s time a great variety of Russian thinkers and writers, despite significant differences in their views, have discerned in the Western mind a fatal split that has rendered modem Western civilization profoundly inhuman precisely in its humanistic endeavors. They all believe that the blame for this split is due to rationalist thinking. For instance, by the end of the 19th century Vassily Rozanov made the following comment, quite typical in its own way, on the dominance of technology and functionalism in modem life:

“The spiritual development which is provided to m nowadays by the state and society for the most part leads to the destruction of our inner life’s integrity and harmony. We are striving to become virtuosi without being aware that we have developed into cripples”.

It is imperative to remind the reader that the prevailing motivation behind reproaches of this kind,contrary to what many Europeans have surmised, has not been scorn or ridicule of Western civilization but sincere compassion for it. For Soloviov, Rozanov or Ern “the struggle for Logos” represents the struggle for restoring the spiritual (i.e., Christian) foundations of Europe.

There exists an extensive literature on the idea of all-unity in Russian philosophy/23) Here it is sufficient to stress some of its aspects peculiar to Ern’s interpretation of this traditional theme. For Ern, as well as for other key Russian thinkers, the basic condition of “ontological”, or “living” knowledge is the teaching on the unity of the transcendent and immanent aspects of existence put forth by the founders of the Orthodox tradition.

This unity by definition abides within itself; it is the inner core of one’s experience and at the same time the condition of being’s plenitude and integrity. Contrary to Aristotle’s First Cause, it is essentially dynamic, a real source of life and, therefore, the latter5s self- transcendent and creative nature. Ern emphatically affirms that the mind should not identify its essence with any objective “data” and there is no privileged “starting point” for philosophical reflection. The roots of thought must be located in the everlasting presence. Hence the persuasiviness of tradition understood as “the internal data” of mind. External representations must be treated as “symbols” of internal reality, which is antecedent to all knowledge and experience but also in a sense anticipates them. Any transient moment of experience can give access to eternity. The conjunction of the universal and the particular, eternity and the fleeting moment, let us note, is a prominent theme in Soloviov’s writings. The very nature of Logos, according to Soloviov, is “something that does not change in all actual and possible sensations, yet is something much more particular that all our sensations”.

Following the early Slavophiles Ern speaks about the priority of the “inner”, “complete”, “living” knowledge over objective, rational, essentially derivative knowledge. Some historians of Russian thought, notably Rev. V.V. Zenkovsky, consider this theory of two reasons confusing and contradictory. However, the real contradiction, let us repeat, is located not within this theory per se but in the relation between the two types of truth already mentioned: quantitative and qualitative, or hierarchichal. The fact is that the discrepancy between the two types of knowledge is akin not so much to the methods of reasoning as to the structure of man’s cultural practice as it has evolved in history. It is the discrepancy between historical and ontological perspectives,the finite appearance and infinite essence of human creativity. And it is precisely this internal gap in human self-awareness that generates consciousness and makes possible both spiritual striving in human beings and, consequently, religion itself. It is both the condition and the means of man’s self-transcendance.

Ern’s Neo-Slavophile thinking, it should be emphasized, exemplifies perfectly this “post-Hegelian” type of thought that has revealed the inadequacy of all representations. It invokes modern (or rather post-modern) theories of symbolism (here Derrida’s deconstructivism or Lacan’s semiology provide the most well-known examples) where signs and signified objects are involved in relations of non-duality beyond the logical parallelism maintained by classical rationalism. Both post-Hegelian thought and the Slavophile tradition admit the absolute value of the inner, or symbolical dimension of experience, the priority of ”internal awareness” and ”intrinsically complete action”, or “the action adequate to Aion” to quote a favorite definition of Deleuze.

In the 20th century many Orthodox authors have rebuked Soloviov for the impersonal nature of his doctrine of Logos. It is true that the relation of all-unity to the personal qualities of existence is not sufficiently clarified in Soloviov’s writings, though as a Christian thinker, Soloviov would undoubtedly have denied the accusations of impersonalism. Interestingly enough, Em has resolutely added a distinctly personalistic tone to the philosophy of Logos — a change no less remarkable than the transformation of Soloviov’s apparent “universalism” into his own apparent “nationalism”. This was made possible since for Ern ontological reality as constituted by the Will is related to “the inner tension” of spiritual ascension. Let us recall that for Soloviov the object of supreme knowledge is the continuity within extreme particularity. Now it is precisely the Will that acts as a principle of differentiation and self-transcendence. The Will, having no self-identical essence, does not “express” itself nor does it possess any static “reflection” in the external world. It is pure action or rather the infinite efficiency of action, which produces not things but patterns while leaving no visible image of itself. By bringing together subjective and objective dimensions of existence in creative acts the Will puts a certain unique,i.e.,personal “stamp” on actual events in the world. Thus it makes possible for a person to transform himself into an atemporal type. This personality-type is as different from the modem notion of the self-enclosed personality as qualitative truth- Logos is different from the quantitative truth of logic. In actual life it is represented, in fact, by the succession (potentially infinite) of moments distinguished by the same personal quality. It is the type of personality we have in mind when we speak about “the spirit of tradition” derived from its founder. It represents the immortal qualities of personal experience embodied,for instance, in holy relics — the objectified essence of the transcendent Will. Ern is quite consistent with his personalistic theory when he claims that the highest achievement of the Will is saintliness — a personal and therefore infinitely variable mark of immortality. In fact the most eloquent testimony to the truth of the Orthodox tradition has always been the presence of “holy men” who have served as objects of universal veneration and emulation. Ern offers his rationalization of this tradition:

“The appropriation of truth is not a theoretical but a practical endeavor;

It derives not from the intellect, but from the Will. The degree of knowing corresponds to the degree of the Will’ s tension. The highest knowledge is accessible not to scholars or phlosophers, but to saints”.

“The Way of the Saints is the way of the heroic Will,which appropriates the possession of the New Earth through the grace of its ascension to Heaven”.

The Will means, of course, inner integrity; it is both the condition and the contents of internal awareness, the essence of self-knowledge. But the Will is also essentially selective: it provides us with the capacity to distinguish between what is projected by the subject (in terms of the early Slavophiles ”what is me and myself») and what belongs to reality (as the Slavophiles put it, ”what Is me and not of myself»). Thus, the Will functions as the principle of distancing and differentiation, in short,as the condition of the plenitude of being. Thus, it makes possible the appearance of consciousness in as much as consciousness presupposes the experience of inner discontinuity.

In the Slavophile tradition inherited by Ern the Will delineates the distinction between types of knowledge and thus defines the entire mental hierarchy of human existence. In the final account it becomes an essentially non-willing Will similar to the Nietzschean “Will to Power” whose nature, according to Deleuze, consists in ”creating not entities but types” and whose destiny is to lose itself within the inconceivably delicate web of reality with all its subtle gradations of difference. This means also that the Will exists prior to all objects; it is a kind of noumenal reality, a general background, a non-generating (or rather difference-generating) source of existence that makes possible the recognition of the inner continuity behind all visible changes. The Will exists prior to all essences, having neither beginning nor end. Being uncreated and yet accessible to humans, it represents the medium wherein the human meets the divine.

We must conclude that it is indeed the limit of all beings that makes possible the being itself rather than the other way around. Everything is indeed only a symbol — a sign which brings forth the experience of limit and thus the conditions of its survival The ”inner integrity” of Will is given only symbolically: it is anticipated or ”revealed” through insight and intuition, ”given” or “grasped” before any knowledge and experience, but is never represented. And the less we are able to formulate verbally the nature of this creative Will the more we are aware of its incessant workings. This kind of mysticism — familiar, it should be noted, to many religious traditions — is the foundation of the Slavophile philosophical apology for Orthodox Christianity as the nucleus of the Russian tradition. This apology is not based on any sort of theological or cultural dogmatism. It makes no overt appeal to the Orthodox Church as a worldly institution. No wonder that Russian adherents of Logos from Kireevsky to Em criticized Western Churches for their excessive dependence on external authority: the political power in case of Catholicism, and power of Ratio in case of Protestantism.

This perspective has also shaped Orthodox views on the nature of the spiritual unity of the Church as embodied by the concept of sobornost, or “organic togetherness” put forward by the early Slavophiles. Ern’s close friend, the Rev. Pavel Florensky, pointed out that sobornost cannot be reduced to the spirit of communion and still less to a practical consensus among members of the Church. The Church represents a vertical or celestial dimension of human existence; it is the visible image of eternal life in Heaven. The Will safeguards this hieratic dimension of spirituality both in terms of individual experience and the historic existence of the Church.

In the light of the hierarchical structure of human Praxis social theory ceases to be descriptive, i.e., «positive”, and becomes instead critical and evaluative. One of the great lessons of the philosophy of Logos is the obligation to distinguish not only between the Church and the State, but also between Politics (and Ideology) and Culture. Such a division can serve as the only valid foundation of social pluralism and, In the final reckoning, the freedom of the individual. In this case Culture would find its real meaning in confirming the interior sacred space of the Will’s working.

The outcome of the dichotomy described above is the hierarchy based on the degree of sociality’s interiorization, the «inner community» of the Will being the necessary precondition of human society. This is by the way, the essential meaning of the traditional Russian ideal of “Holy Rus” — the internal and spiritual image of geopolitical Russia. The early Slavophiles themselves had suggested that the Russian people had lost their integrity because, having lost the sense of inner communion, they mistook what is expressed for expression itself. It is easy to expand upon this penetrating observation: the sudden discovery of the falsity of the traditionalist commitment to the past accounts for many a violent break with their own historical legacy exhibited by Russians over the past two hundred years. Yet these upheavals have not been without their lessons. They have brought to light the moment of oblivion of culture’s symbolic depth. This oblivion signifies the coming of modem positivist civilization with its dichotomy of spirit and matter, reason and faith,the psychological ego and the physical world. From the perspective of the «free theosophy” of the Logos, the positivist identification of reality with the world “out there” was not a misperception limited to the Russians, but, in fact, represented the common outcome of humanity’s Fall.

Ern’s philosophical position, therefore, seems to be both a powerful challenge and a corollary to the modem technocratic «civilization of appearances.» It restores our link with the internal continuity of tradition without forcing us to discard human history. Rather, it encourages us to search for traditional values in the future in the creative workings of the Will. It shows the way out of that quintessentially modem boredom which is rooted in the experience of life reduced to what Paul Valery called «rien infmiement riche.” It would not be an exaggeration to say that reflection on the Logos of the East opens a new perspective on understanding tradition as a viable global alternative to the civilization of modernity.

Beginning with Durkheim, most sociological theories have been based on the opposition between a structured society and social anarchy triggered by ”anomie” with its sacred orgies. The works of Durkheim’s pupil M.Mauss gave impetus to the investigation of “direct” and intimate social communication by means of “transgression”. The idea of transgression is indeed a great theme of Russian cultural history where transgression sometimes overshadows the legal foundations of society. The philosophy of Logos calls for introducing a third type of sociality different both from the civil (political) society and the pure collectivity of the crowd immersed in ”transgression.” Such a sociality combines the autonomy of the individual with the primacy of social existence. This union is as divine as it is natural and is not imposed on people since it belongs to the nature of consciousness itself. It only lacks the quality of publicity and, consequently, the situation of human self-alienation. The legacy of the Russian Logos belongs to those great traditions of humanity which highlight «sacred silence’’ as the highest virtue and the culmination of moral behavior. This profoundly meaningful silence is the most adequate expression of the fullness, or perfection, of man’s being.

The sociality of Logos is neither an institutionalized society, nor the Church community as it appears in history, i.e., in its transitory and conditional forms. Neither is it a non-differentiated unity of the crowd. Rather, it is a personalist experience discovered in the depths of internal life, a pre-condition of human intersubjectivity, a sociality transformed into a type. Just because it refers to the relationship constituting the core of personality transformed into a type or,rather, reduced to its core as a persona, this sociality can be understood as being related to the uniqueness of Divine Humanity — namely the life of the Church as the mystical body of Jesus Christ. And, just like corporeal awareness, it encompasses the unlimited range of typefied experiences which constitute personal immortality. Ern quotes in this connection the amazing words of the Gospel: “in the house of My father there are many mansions”. Spiritual perfection is tantamount to freedom because it opens up the infinite world of infinite possibilities. Spiritual life is ascetic because it requires being open to all of these possibilities. This is the reason why ascetism is considered in Orthodoxy the source of supreme joy.

Here we are discovering one more important aspect of Ern’s philosophy of Logos: the exaltation of freedom or, to be more exact,free commitment. This discovery might come as a surprise since rationalist thought has been perceived as promoting liberalism of all kinds while traditionalist thinking has been associated with dogmatism and intellectual stagnation. Ern overturns this argument. He claims that neither the transcendental nor dialectic methods in philosophy can produce a viable idea of freedom though he praises Kant’s commitment to the cause of human liberty and even finds in it the proof of Kant’s geniality. It is obvious by now that for Ern the hegelian concept of freedom as intersubjectivity is lacking a “Heavenly” (ontological) dimension and is, consequently, too shallow. The real significance of freedom, according to Ern, lies in the conscious and responsible acceptance of the divine fullness of Being. Such acceptance is as free as it is compelling, responsible and courageous, even heroic: it presupposes the acceptance of one’s own death, or rather one’s liberation through death (a prominent theme in the Orthodox tradition). And yet this affirmation of the divine plenitude of Being, while being an act of the free Will, also partakes of the non-affirmative nature of absolute freedom which corresponds to the primordial, or “paradisaic”, condition of humankind. Genuine liberation is an act of self-transcendence, a promised perfection.

So, the liberating effort of man and divine freedom finally converge into a unity. This kind of a non-metaphysical differentiation or, better say, non-duality of finitude and infinity in human existence accounts for a remarkable freedom for man in his choice of action and his whole life style. In practical terms this idea of spiritual transformation as the non-duality of Heavenly and Earthly existence endows concrete actions with the significance of eternal types. Hence the great variety of social attitudes sanctioned by Russian spiritual tradition, a variety which does not at all exclude a deep and sincere commitment to the perfection that each particular situation calls for.

Strange as it may sound, the philosophy of Logos makes possible human freedom in a non-liberal context of the working of the Will. The Will itself acquires here the character of non-willing. This conception of freedom can be, no doubt, a powerful humanistic factor in a world where being human means to safeguard the immeasurable symbolic depth in man.

The Metaphysics of Action: Depth History

The theory of history came to be one of the most hotly debated issues in the polemics between Ern and his Neo-Kantian opponents in Russia. The editor of the journal “Logos”, Hessen, in his review of Ern’s book, The Struggle for Logos, mounted a scathing critique of Ern’s historical views. Hessen accused Ern of a utopian desire to reach the perfection of knowledge in one stroke, while dispensing with its limited and conditional forms, such as legislation, politics, economic organization, etc. Following Hegel’s criticism of Schelling’s intellectual intuition, he asserts that Ern’s thinking is permeated with “empty depth, a tension devoid of contents” and, therefore, it renders meaningless any idea of development. Here, Hessen concludes, “pathos replaces reason”.

Hessen, as we shall soon see, completely misunderstood Ern’s position; nevertheless, he was right in qualifying the idea of “depth” as the basis of Ern’s historical theory. For Ern this depth was, of course, far from being empty. In fact, it was the very foundation of a real history, the metaphysical condition of history. An instructive and beautiful passage illustrating this point can be found in Ern7s lecture which bears the title “Time is Slavophiling.” It was delivered in February of 1915, when the First World War was raging:

“All who are of a bright and heroic brand in Russia, responding to the call from on high,humbly stand up,leave their parents, their whole way of life and start on n journey to the suffering heart of their motherland wedded to Christ. And all who walk along this road of purification and sacrifice, having reached a certain limit,suddenly disappear from view… The seeds of divine abundance are being covered, as it were, by the earth; they grow and bear fruit in mystery,in calmness and some place hidden from external looks”.

For every Russian with at least a minimal knowledge of the Orthodox tradition these words immediately strike a familiar note. For Ern is speaking here of the very core of Orthodox spirituality — the process of man’s deification: man becomes what he is through his path to God. This view of human life — central to the new philosophy inaugurated by Soloviov — presupposes that history should be judged in terms of the self- liberating spiritual perfection inspired by “the divine fire of creative love” (to quote the words of Era’s contemporary S. Bulgakov) which brings about the transfiguration of the material world. Evidently, this approach to history does not negate actual development but exposes the latter’s inner limits as determined by the logic (or rather Logos) of the Will’s work of personalization. For the workings of the Will posit the non-duality of finite action and infinite activity. As the title of Ern’ s lecture indicates, this inner and spiritual quality of development is meta-subjactive; It Is disclosed by the circumstances of the moment itself which unfolds, as it were, into a mysterious opening, becomes a door onto eternity. At this edge of the humanist world human deliberations are left behind and, in the words of the Russian poet, Boris Pasternak, “the soil and fate start breathing.”

Ern’ s historical theory bears the evident influence of the ancient Orthodox concept of metanoia (changing or transcending the Mind) which indicates the passage from an external empirical/rationalist perspective to that characterized by an internal and spiritual vision. The real transformation that Ern speaks about here has an inner depth that is essentially symbolical. It is a change within change and has the nature of selfconcealment, “going inward” (or upward for that matter). Such a purely qualitative change cannot be explicated by any “objective data nor can it be observed and measured. Its goal is contrary to Hessen’s comment on Ern’ s alleged “subjectivism”, is precisely the overcoming of all forms of subjective pathos and the achievement of the state of apatheia, or freedom from psychic impulses, which are inevitably conditioned. The contemporary Orthodox theologian V. N. Lossky calls this spiritual transformation “the mystery of the Eighth Day of Genesis”, “the perfection of gnosis whose fullness cannot be realized before the end of this world”. Indeed, this perfection of knowledge is equated in the Orthodox tradition to the Second Coming of Christ. It constitutes the real meaning of history and is accessible to saintly persons even in their earthly life. An authoritative Byzantine writer of the 13th century, Simeon the New Theologian, commented on this idea with the following words:

“For those who have become the children of the Light and the sons of the Coining Day, the Advent of Christ will never take place because they are always within it already. The Day of the Lord will happen suddenly to those who are plunged in the darkness of passions and love the favors of the world. For them it will come all of a sudden and will be terrible like a tormenting fire…

Man, continues Simeon, can reach salvation even during his life if he accepts fully and with the utmost sincerity the Lord’s judgment in the depth of his heart.

We can conclude now that in the Orthodox tradition historical time should be conceived as essentially a double-poled reality, a sort of intermediary space which brings together two aspects of being: the finitude of man’s sinful (physical) nature and divine infinity. In the end there does exist a continuous forward movement in such history — the path toward universal perfection. History is nothing short of the fulfillment of creation. Such a development occurs both in history and at the same time transcends actual existence. It represents, according to the observation of J. Gaith, “the slow constitution of the world which reproduces,through particular destinies, the general move onward”.

So history for Ern does have an essential content and a definite vector of development — an ascension. But it is essentially the succession of self-substantiating events, the history of tradition which cannot be reduced to a story. Such a history accounts for Itself and cannot be translated into dialectical schemes, though, perhaps, it can be explained by them. An important issue to be addressed here is the observance of the proper balance between the mundane and the divine or, to speak from a phenomenological point of view, the maintanence of symbolic dimension. The desire to bridge the gap between Heaven and Earth proved to be,as the history shows, the main force behind the radical secularization of Christian eschatology and the formation of the revolutionary ideology which evolved m due course into bluntly de-humanized totalitarian ideologies. In fact, this “evolution” determines the meaning of modem history. The most important task in the contemporary world, even for the sake of preserving humanist values, is the restoration of that symbolic — both infinitely small and infinitely great — distance between the spiritual and physical that makes possible a real evolution of humanity.

In Ern’s later work on the Italian Catholic thinker V. Joberti we find passages which look like a reply to Hessen5s criticism of Ern’s “empty subjectivism.” Ern, as usual, takes the offensive as the most effective means of defending oneself: he claims that Hegel’s philosophy, despite its dialectical method and its stress on reality’s self-development, is characterized by an Inner lack of dynamism. This is due to Hegel’s inclination to recognize only “phenomenal” change related to human subjectivity. This great dialectician, Ern argues, is heir to Kant’s static anthropocentric vision, which leaves no room for human development. Ern has in mind3 of course, the event of metanoia mentioned above. In Hegel’s system, Ern continues, cosmic, psychic and dialectical processes all exist but there is no real history. The subsequent Marxist reduction of history to economic development was the inevitable outcome and a clear proof of this absence of actual historicity in Hegel’s thought. Generally speaking, Hegel remains trapped in the prison of modern anthropocentrism. Moreover, his dialectic presents, perhaps, the most sophisticated version of this modernist dead-end.

It should not come as a surprise now to realize that in Ern’s view, it is the mysticism of Logos and not Hegel’s dialectics that links becoming, change and each and every singular event to ultimate reality. The philosophy of Logos, according to Ern’s view, affirms “the positive metaphysical idea of history”. It represents essentially an ontology of change. That is to say, it affirms the change of change, the change within change, the continuity of transformation, “the internal quality of the historical movement” This is where we discover the real significance of symbolism in Ern5s thought. Symbolism refers here to the ontological and,therefore,always absent in the phenomenal world dimension of event. It postulates the noumenal counterpart of all appearences and the matrix of all activity, itself non-changeble. Ern recalls the image of the “dove’s eye” to convey the idea of thought’s invisible ontological depth (or rather height). He borrows from the 18th century Ukranian thinker G. Skovoroda the comparison of thought to “the snake that creeps on the earth but possesses the dove’s eye that looks above the waters of the Flood at the beautiful essence of truth”.

So it was by no means accidental that Soloviov’s doctrine of Logos exerted the most profound influence on the literary movement in Russia which came to be known as Symbolist. In fact, one of the most important lessons learnt by Russian Intellectuals from the philosophy of Logos was a clear understanding that Symbolism has its own efficient and reasonable rules, even though these rules are essentially different from the external and quantitative laws established by the natural sciences. Symbolic thinking asserts the non-duality of things in particular, the coincidence of opposites; it postulates internal unity within manifest variety. This law operates in the transformational symbolism of the Christian Eucharist and in the cult of holy relics conceived as the embodiment of spiritual power. It was precisely the nature of traditional Christian symbolism, Ern asserted, that remained completely incomprehensible to Hegel’s Protestant mentality. Ern formulates this law in the following words:

“The wisdom of Heaven and the wisdom of the Earth in some immeasurable distance, beyond all limits of our narrow horizons, converge in. one immeasurable divine Mystery. And yet, though converging in this incommensurability these two wisdoms are by necessity separated for those who contemplate them from here.

Moreover, in the initial stages of contemplation they can be separated to the point of mutual hostility”.

The law of “mysterious conjunctions” allows precisely for this meeting of opposites since from its perspective things are identical not by their formal similarity but by the very limit of their existence. Spiritual and physical worlds converge in the act of their transformation, i.e. in their self-transcendence. So Heavenly perfection according to Ern can be and symbolically is actually united with the transitory nature of Earthly life. What is absolutely constant in human experience, to recall Soloviov’s formula, coincides with the extremely particular. History is an answer to its own teleology.

But the “mysterious conjunctions” mentioned above are not to be attained without a price: such an event requires the recognition of history’s limits. History as the fullfilment of Logos, or the absolute becoming, Ern argues, is constituted by continuity and this is the reason why it cannot be reduced to a story, to a specific narrative. Contrary to Hegel’s image of history as the unfolding of one transparent logical structure, for Ern, history is regulated by the infinite and yet qualitively distinct, internally determined, m-determined event of self-transformation. In the light of this transformational metaphysics, every historical moment presents itself as an echo of the same eternal call, a shadow of the same invisible face. History is conceived here as an intricate web of self-sufficient and, therefore, esthetically significant moments of experience (scarcely ever static appearances) which bear witness to hidden and all-embracing growth. It is determined not so much by appearances as by the gaps between observable facts. Material existence is no enemy to spiritual life. The philosophy of Logos allows even for the apparent desacralization of human practice and the triumph of technological civilization in modem times to be interpreted as a testimony to the consolidated ascension of humanity in the symbolic depth of humankind’s existence. The symbolic truth of philosophy and the positive truth of science can and indeed should be reunited as mutually complimentary aspects of human experience in the phenomenology of Logos.

History as a realization of a “positive metaphisical idea” never stops working. But this progress, as Ern often reminded his readers5 affirms discontinuity; it has, therefore, a catastrophic nature. This kind of “depth history» remains unwritten — precisely because it is being written out by the lacunae in actual existence. The history of Logos in the final reckoning justifies Christian eschatology. Em evidently elaborates here on the apocalyptic vision of the later Soloviov but he overcomes the latter’s pessimism, which, perhaps, like so many other traits of his philosophy is more apparent than real. It should be equally clear that what is referred to as “catastrophic progress” in Ern’s historical theory should not be confused with “revolution” carried out by materialistic means for materialistic purposes. This catastrophe affirms the very openness of the future.

Ern was anxious to verify his concept of “historical metaphysics” in Russian intellectual and cultural history and in fact suggested an original approach to the Russian tradition as a sort of “internal succession” of spiritually enlightened minds. This perspective actually helps to explain some fundamental features of Russia’s history such as the drastic, at times truly “catastrophic” changes in Russian mentality or the obvious disparities between different spheres of Russian civilization, especially in the imperial period: mystical Orthodoxy centered around monastic life, the secular and humanistic culture and the technological systems existed in Russia to a great degree independently and no solution was seen to the confrontation between the sacred and the mundane forms of ideology in Russian society. The reconciliatory stance of the new philosophy of Logos came too late and was virtually neglected by the wholly secularized Russian intelligentsia.

Let us draw just one example which serves to highlight the deep ruptures (which are not amenable to logical articulation) within Russian culture and the Russian mind: the construction of St.Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square in Moscow in the 16th century. The cathedral remains the most famous symbol of Russia’s specific type of saintliness. There is a remarkable discrepancy between the playful and purely decorative qualities of Cathedral’s exterior and the dark and narrow corridors and cells of its Interior. This perplexing discontinuity reminds us that the Russian idea is typically either a decoration existing ”out there” beyond substantial form, or ”down there” in the inaccessible depths of inner awareness where man communicates with divinity. The integration of these widely divergent aspects of life remains the most urgent and formidable task of Russia’s quest for self-identity. The philosophy of Logos opens a plausible perspective for arriving at a comprehensive understanding of Russian traditional spirituality.

No wonder that Ern’s philosophy has exerted a profound influence on virtually all Russian thinkers who have been concerned with restoring and developing the viability of the Russian tradition. One of these, A.F. Losev, was the leading non-Marxist philosopher inside Russia whose seminal article entitled “Russian Philosophy” published in 1918 focused on Ern’s thought. Em’s “catastrophic” theory of history greatly influenced later Russian thinkers interested in Christian eschatology: Florensky, Berdiaev, Bulgakov, and Florovsky.

Ern’s views, however, have much broader applications for philosophic reflection and especially comparative philosophy. It should have become clear by now that this alleged proponent of “Russian nationalism in philosophy” has in fact worked out an even more coherent and persuasive version of Soloviov’s universalistic outlook. In fact, Ern’s philosophy of Logos asserts not so much the dualism of East and West as the hierarchy of philosophical truths at the top of which stands the mystical relationship between the knower and the known, the noumen and external reality — a relationship referred to as Logos. Western “rationalism” in Ern’s opinion corresponds to the dissolvement of this comprehensive synthesis and the ever-deepening conflict between transcendental and empirical values. Yet we should hasten to add that “transcendental reflection” is just one possible means that has lead to the corruption of Logos which can be observed in modem Western thought. There is another possibility for the decline of Logos,namely the attempt to objectify the very premise of the symbolic matrix of experience and consequently arrive at a dogmatic equation of the spiritual and material dimensions of being. The outcome of this sort of “mystical dogmatism” would be a blind conservatism in culture and the dominance of violence in politics since no rational procedure for the reconciliation between the inner and the outer dimensions of existence is available here. The confrontation between violence and passivity is of itself a tremendous obstacle to the creation of political and cultural integrity in society. These fallacies are quite typical for Russian civilization. So “the struggle for Logos” should be posited as a remedy against specific Russian evils as well.

Whatever the merits of the approach to cultural history proposed by Soloviov’s and Ern’s mystical philosophy of all-unity, it posits some serious challenges to philosophic reason. It demands from modem man confidence in the workings of the Will and the effort required to transcend all «objective grounds» for this creative process — simply because it is creative. It demands the acquisition of the wisdom of living by inner experience in the world reduced to objects and signs. It demands, finally, to be aware of the dividing line between public society and the inner sociality of Sobornost.

Curiously enough, the actual course of the development of modem philosophy has been determined neither by classical rationalism nor by the idea of divine Logos. Rather, contemporary thought has discovered an abyss within “the Word of Reason”. This does not necessarily contradict Ern’s concept of “catastrophic progress” but requires the latter’s radical reformulation. The struggle for Logos initiated by Ern in the name of Soloviov’s apocalyptic vision has become by now the struggle for saving Logos within its own abyss.